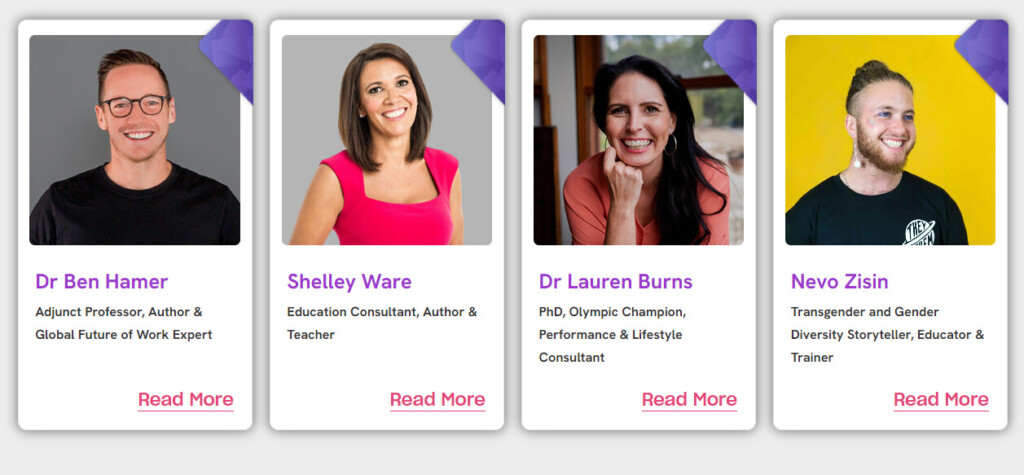

October 2018 saw the release of the latest report from Victoria University’s Mitchell Institute. Authored by Bill Lucas and Charlene Smith, it takes a ‘whole of life’ look at how capabilities can be cultivated starting from the early years, through schooling, and beyond.

What are the modern capabilities?

The concept of personal capability, and how to build it is not new. However, in recent years, the concept has been “rethought and reinvigorated”. And, as the report says: “Capabilities have the potential both to prepare students for an uncertain world and to enhance enjoyment, engagement and achievement throughout learning.”

The report identifies a few key capabilities. They include deep content knowledge, core skills such as literacy, numeracy and Information and Communication Technology (ICT), as well as life and learning skills such as critical and creative thinking, personal and social capability and both ethical and intercultural understanding. They are made up of ‘knowing what’ – the knowledge – and ‘knowing how to’ – the skills – leading to the development of capabilities along with a set of enabling personal habits and dispositions.

This process begins in early life and continues right through. Schools provide an important foundation, as does family. Beyond school:

“Universities and vocational education and training (VET) providers across Australia are also giving increased attention to the cultivation of capabilities. A focus on the relationship between skills, knowledge, mentoring, and practical opportunities to apply and demonstrate learning, will enable education systems to support continued development of student capabilities.”

Another perspective on capabilities – the so-called 21st Century skills – is provided in a paper by Steven Lamb and his colleagues, who are also based at Victoria University.

Strategising to develop capability

The report proposes eight steps to strengthen capabilities. The first is to make a strong, evidence-based case for the value of capabilities to employers, parents and educators. Employers and parents are particularly important. However, educators need to step up and be “better prepared to teach, measure and assess capabilities from early childhood onward.”

The next step involves seeing the development of capabilities across education sectors. Capability development is a lifelong task after all! Third, it needs to involve a process of simplification because “teaching capabilities can become complex and confusing.” Next, they advocate the development of “case studies” of how to foster such capabilities through the learning process and also through ‘exemplar resources’ and support materials for educators – including guidance about “approaches to teaching and learning which are most conducive to cultivating particular capabilities.” These approaches might include problem-based learning, the development of learning communities and even ‘playful experimentation’.

Building on the case studies, Lucas and Smith suggest that professional networks need to be developed to share effective practices. The difficulty in Australia in my view, though, is sharing such practice across sectoral boundaries. Another of the critical aspects is that when capabilities are not assessed they are not valued. To respond to this, the authors suggest a need to:

“Draw on existing promising practices to create guidance on the assessment of the general capabilities.”

Their last two strategies involve, first: providing support for educational leaders to actually lead the development of capabilities and – finally – creating “an evidence base for all aspects of the implementation of the general capabilities to promote sharing, innovation, and widespread practice improvement.”

The authors’ priorities for the ‘ways forward’ in fostering capability development require a commitment to long-term implementation, support for the education workforce and taking a strategic approach to the measurement and assessment of outcomes.