NCVER has just published Unpacking the quality of VET Delivery by Hugh Guthrie and Melinda Waters that looks at issues in quality delivery and how it can be measured.

What makes for quality delivery is context dependent in a diverse sector like VET. Measuring it can be tricky too.

What do we know about quality and how to measure it?

The answer is actually a fair bit, and so ‘Unpacking the quality of VET delivery’ is the first product of an NCVER-funded project which focuses on quality issues in how RTOs deliver on VET services and products. It draws on the wide range of literature on the topic and is a prelude to the project’s final report. The project seeks to answer questions about “what good-quality delivery involves and how it might be better measured, sustained and improved.”

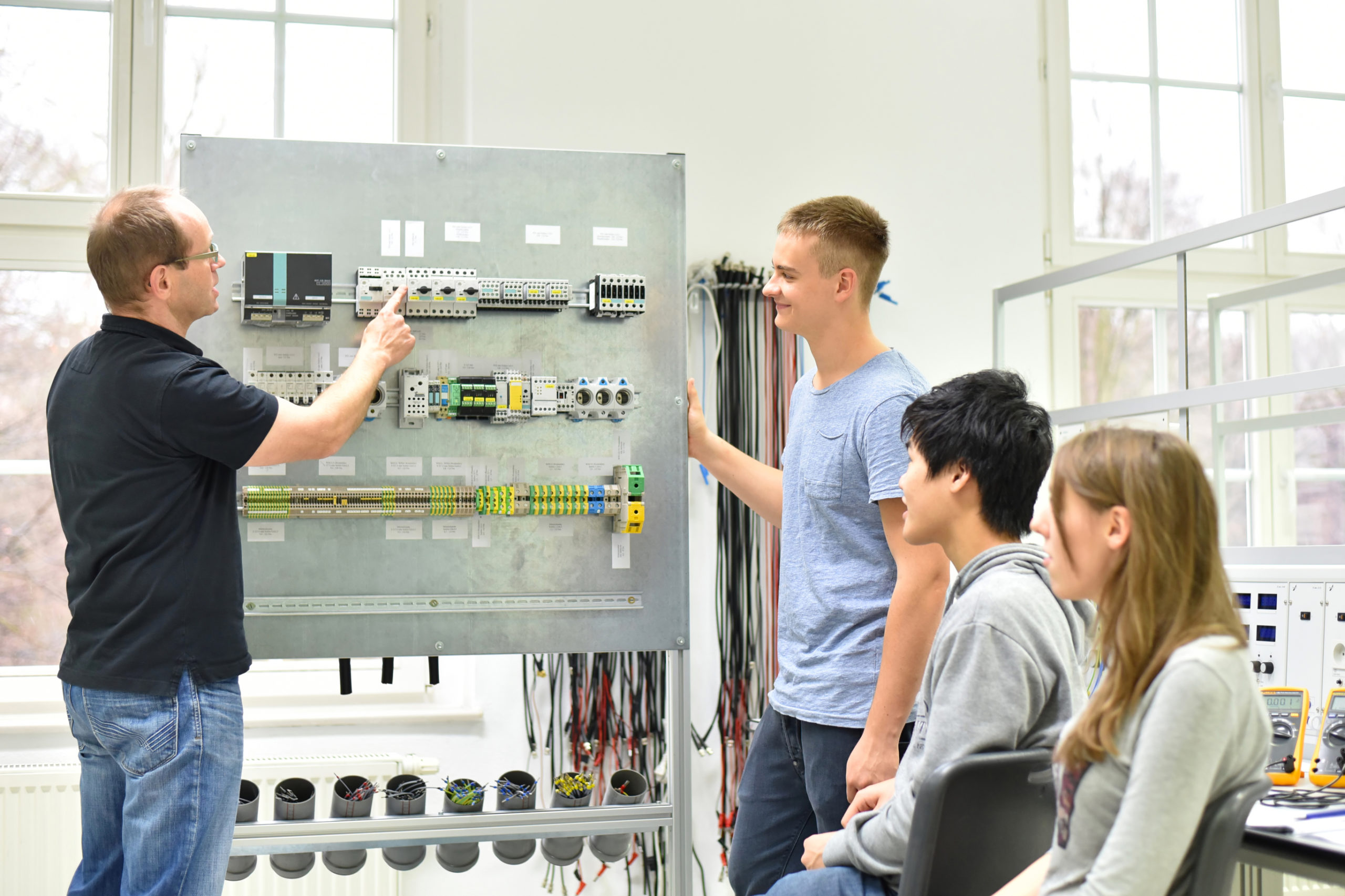

While many stakeholders in VET are concerned with the quality of delivery it is in RTOs that delivery quality is made or broken. This is where the project has concentrated: gathering the provider voices in all their variety, given that other voices are being heard through the extensive consultations on VET reform that the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) are undertaking. We have highlighted this work in earlier editions of VDC News, which you can access here, here, here and here.

What the paper says

The authors, Hugh Guthrie and Melinda Waters, point out that ‘delivery’ is a broad term. It “extends beyond teaching and learning to the whole student experience − from before enrolment, through to completion and beyond − and involves a range of educational and support services.” It’s also complicated by the different ways VET’s many stakeholder groups think about what VET delivery is for and what its ‘qualities’ are. There are also a multitude of factors that impact on the quality of delivery within and outside RTOs.

A number of measures, often quantitative, are routinely used to evaluate the quality of delivery at national, state and VET provider levels (e.g. enrolment and attendance data, graduation rates, attrition rates, student and employer satisfaction to name a few). However, there are concerns about the extent to which these measures fully capture the complexity and diversity of VET’s delivery contexts or reflect those really important aspects of delivery quality that make a difference for individual students and employers. This is because, in VET, “some see the quality of delivery primarily in terms of outcomes, others as a property of the delivery process, and yet others in terms of value for money or return on their investment in the system.”

The range of RTOs’ contextual factors, organisational foci and missions also means that a ‘one size fits all’ set of measures of delivery quality may not serve all purposes. Thus, the range of provider types: TAFEs, private, community education and enterprise will share common attributes of quality, but there will be differences too. These are affected by their respective ‘missions’, the courses offered and the types of students they enrol. Size also matters, because size often brings with it a diversity of offerings, student groups, sites of delivery and other complexities. So, the authors suggest “Our initial thinking suggests that it may be better to consider ranking or rating discipline areas rather than institutions overall, particularly where RTOs are larger and have diverse profiles.”

Defining quality and the quality of delivery is therefore not simple and measuring it involves gathering and using a wide range of data and information − both quantitative and qualitative − throughout the student life cycle to develop a ‘true picture’ of quality. However, Hugh and Melinda suggest that a balance needs to be struck between meeting immediate needs and developing students’ longer-term skills, as well as the personal capabilities that will sustain them through their careers.

The authors also point out that:

“Critical factors affecting the quality of delivery include the policy and regulatory milieu in which RTOs operate, the quality of training packages and the ability to translate them readily into training programs, the types of students, the availability of teachers and trainers, the quality of leadership and culture in RTOs, and the effectiveness of initial and continuing professional development in maintaining and building the quality of RTO workforces.”

These issues and challenges have been identified in the literature for some time. So, what seems to be needed is a set of strategic and comprehensive interventions to shift the tenor of the quality delivery debate in VET. We also pretty much know what the problems are. There is also advice going back a number of years on what might help fix them. What seems to be needed now is less words and more action.

Linking to other useful stuff?

Over the last few issues VDC News has been going back in the ‘annals of time’ to look at a range of issues associated with the quality of delivery and how quality might be improved. This includes recent and past work aimed at reforming VET qualifications, developing so called Centres of Vocational Excellence to help promote exemplary practice, quality case studies in VET providers in Victoria, getting and keeping VET teachers, summarising an extensive body of work that looked at what was needed to enhance the capability of VET providers and, finally, ‘niggling, jiggling and squidding’ to improve practice.