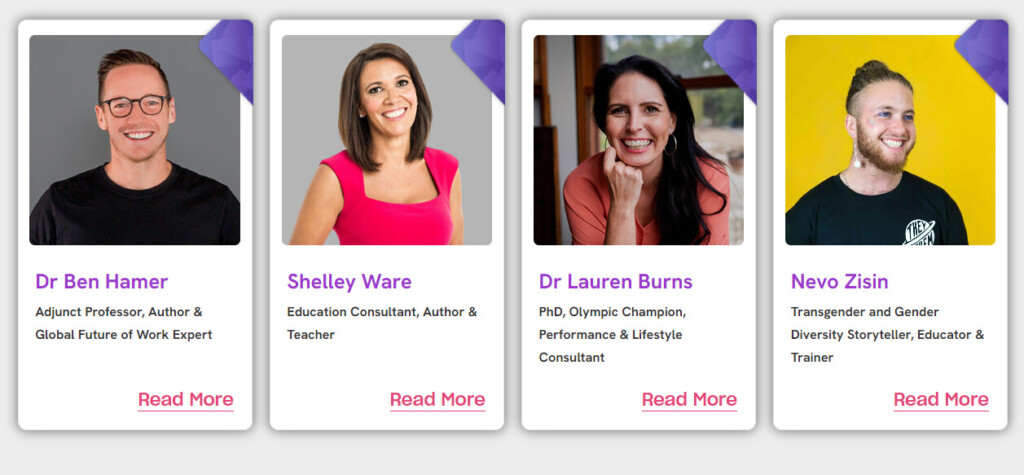

Sponsored by the Centre for Vocational and Educational Policy at the University of Melbourne, Shelley Mallett and Diane Brown from the Brotherhood of St Lawrence present their ideas for radical changes in governance, institutional arrangements, funding and in the core educational philosophy underpinning the sector.

Their argument is that VET is largely failing to equip young people for meaningful work and supporting lifelong learning.

Their PowerPoint presentation and a video can be found here VET and young people.

VET: its changing mission and focus

Shelley and Diane suggest that VET has moved from the broad conception of vocational education envisaged by Kangan in the 1970s to one that is far narrower and more instrumental: that is, one which saw the sector as providing productive citizens to one which sees it as the ‘engine room for industry’.

VET also has mixed outcomes. True, there is high student and employer satisfaction, most graduates get an employment-related benefit, qualifications are portable and the sector caters for a large and diverse client group. However, there are low attainment rates, poor articulation between education sectors, issues with the quality, complexity and fragmentation in the market and a parity problem with higher education underpinned by a funding mismatch.

In their view, a key focus needs to be ‘the student’.

A move to person-centred VET reform?

Young people are telling ‘us’ that there is “limited provision of vocational guidance and navigational support in a complex and opaque [VET] system.” VDC News has explored the issue of post-school transitions in a few earlier articles here, here and here.

Students also found an inflexibility in VET’s teaching approach and an artificial separation of vocational and non-vocational needs. Funding schemes also constrain real choice, despite the apparent flexibility of Training Packages, and the pathways through school, VET, higher education or onto work they suggested really don’t actually ‘flow’. And all of these problems are compounded by very real financial and transport barriers to access for young people.

How do some young people see themselves?

They have strengths and skills, aspirations and ambitions, hopes and dreams. They are also hindered by low levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy and motivation, low LLN skills or undiagnosed learning difficulties, limited social capital, insecure financial security and housing and little awareness of their strengths, options and possible pathways.

So, what’s needed?

A training curriculum that enables them to find meaningful employment and to adapt to the emerging labour market. They promote the idea of vocational streams and productive capabilities. In addition, they suggest that what is needed is:

- Seamless pathways through education systems and levels

- Teaching approaches that build skills and self-confidence, motivation and aspiration

- Vocational guidance and navigational support, particularly at enrolment and initial engagement with the sector

- Integrated support services around mental health and both housing and financial insecurity

- Real world opportunities, such as work experience and network building with employers, and finally

- The freedom to change their mind as their learning and range of experiences grow.

After all, work, education and training is for young people especially more ‘crazy paving’ than a clearly defined path.